Telehealth Challenges in Management of solid Organ Transplant Patients the Era of COVID-19-Experience of Virtual Bedside

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought forth significant challenges in health-care delivery, especially regarding the use of telemedicine. Preventing unwanted exposures to high-risk populations such as the immunocompromised transplant patients in the safety of their homes while observing social distancing became imminent.1 However, effective and equitable healthcare requires standardized protocols, which was severely lacking for this new telehealth era. The development of telemedicine delivered through a HIPAA-compliant platform brought accessible and personable health care options to patients at home.2 The ability to access telemedicine platforms through mobile applications increased patient participation by removing technological barriers and enabled seamless virtual patient and provider interaction.

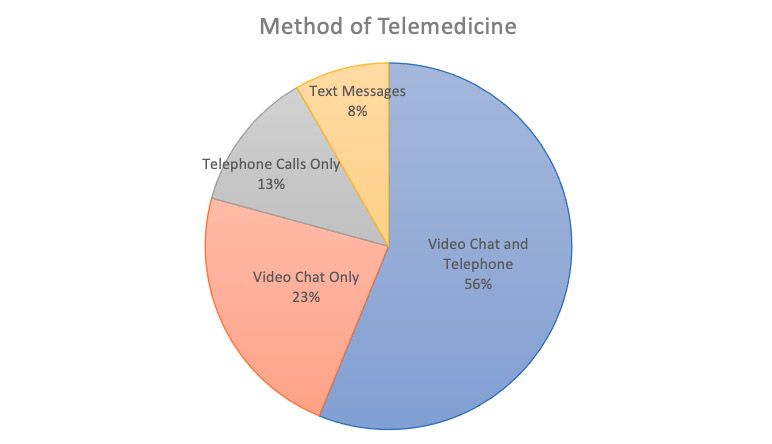

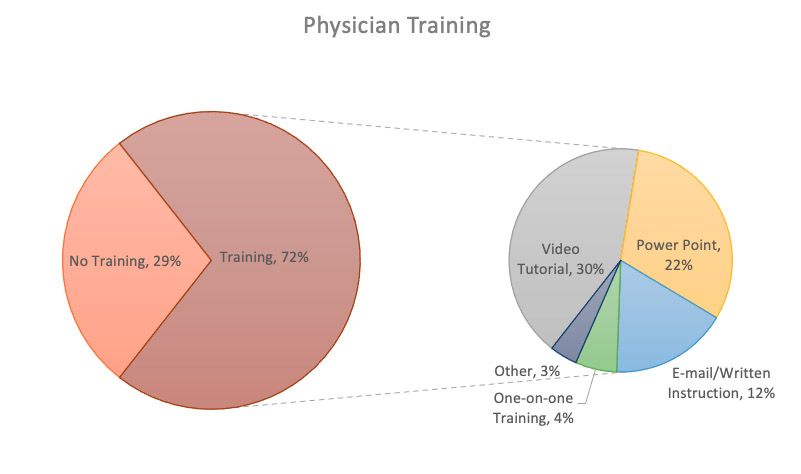

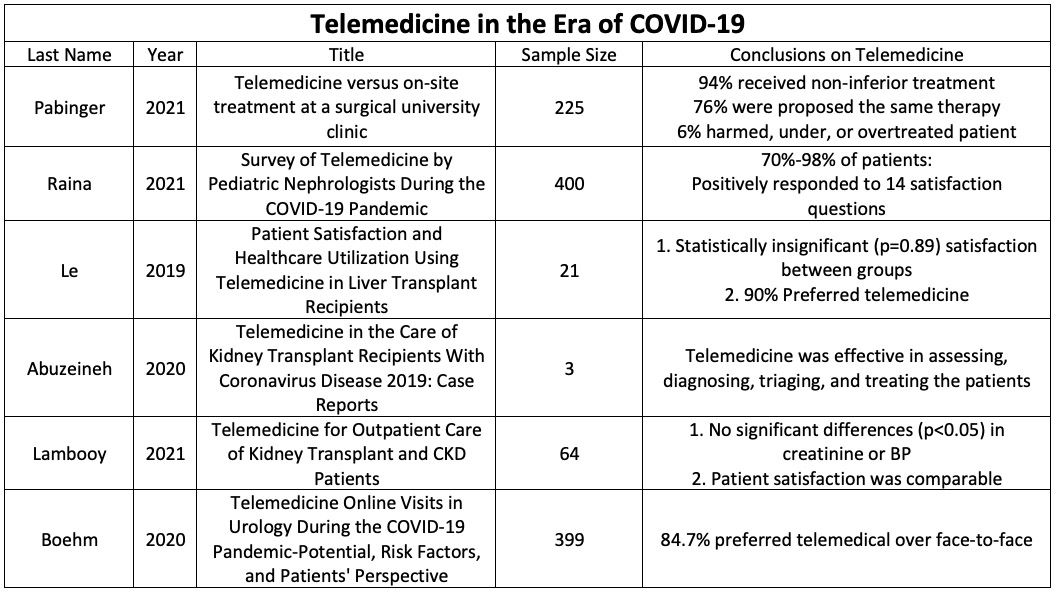

Telemedicine experiences during the pandemic can be summarized by Raina et al. which queried 197 pediatric nephrologists and 400 of their patients about their experiences. Figure 1 shows the preferred modalities for most physicians at 56% using both video chat and telephone calls, 23% using only video chat, 12.4% using only telephone calls, and 8.3% using only text messages. Physicians also used a wide variety of online systems to conduct synchronous telemedicine which included Zoom (23%), EPIC (9%), Doxy.me (7%), services not specified (37%), or a mix of local or smaller services (24%). Figure 2 highlights whether or not physicians received training (n = 141, 71%) in the use of telemedicine services as well as their method of training (42% video tutorial, 31% PowerPoint presentation, 17% e-mail and written instruction, 6% one-on-one training). Overall, the majority of physicians expressed satisfaction with the telemedicine experience with only 5% disappointed in the clinical aspect of telemedicine and only 4% disappointed overall. Most of their concerns were related to technological issues or the ability to view physical exams and/or laboratory results. In regards to the patient, most reported positive experiences as it was logistically easier and faster than in-person visits. Patients also felt that the quality of their visits were equal to what they would receive in person.3

Widespread acceptance of telemedicine services in fields such as pediatric nephrology emphasizes the need for the standardization of virtual care. A standardized workflow can potentially allow for more effective patient care, maintain clinical standards, but more importantly help ensure optimal patient outcomes with minimal risk of contracting COVID-19 or any potential infectious disease. Previous to the pandemic, emerging literature highlighted growing evidence of equal to above average clinical outcomes following the introduction of telemedicine in the postoperative setting. Complication rates were not statistically different between telehealth and traditional follow ups which ranged from 0-4.8% in procedures such as laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, parathyroidectomy, arthroplasty, and pediatric urological procedures.4-8 As of now, no studies have reported statistically higher complication rates with telemedicine visits compared to traditional follow ups which supports its use in a wide array of specialties.9

The University of Cincinnati Liver Transplant Program found that increasing posttransplant care between visits was a top priority for patients to improve function, quality of life, and independence.10 Technology and thereby telemedicine programs have the potential to personalize care to meet the needs of each individual patient. A small pilot study showed that developing a telemedicine-based home management program (THMP) was feasible and effective.10,11 Participants in this program had lower 90-day hospital readmission rates than the institutional and national averages (28% to 58%).12,13 Compared to their traditional follow up counterparts, individuals in the THMP program had significantly improved quality of life for physical function (p=0.02), social functioning (p=0.05), and general health (p=0.05).12,13 Patients noted that from their perspective, the biggest determinant for quality of life is time spent at home compared to the hospital. More importantly, there was no difference regarding health literacy assessments between the 2 groups as 90% of patients scored in the highest group, or ninth grade and above.14 In a similar cohort, Le et al. assessed whether telemedicine can be utilized to sustain strong patient-physician relationships in post-liver transplantation care and came to the same results and conclusion.15

Utilizing telemedicine to diagnose and triage patients has also shown great success in kidney transplant recipients, providing uninterrupted follow-up care to these high-risk individuals. Abuzeineh et al. followed three kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19 that were managed using telemedicine and found that this allowed transplant clinicians an expanded opportunity for patient questions, transmission of information, reassurance, and creating a sense of building a comprehensive care plan.16 By extension, this innovation could potentially help increase access to live kidney donor transplant evaluations, particularly important to those who have financial or transportation challenges.16 These concepts are reinforced by Wilkinson et al. which examined a similar situation in terminally ill cystic fibrosis patients awaiting transplantation.17 All of the telemedicine participants found that this modality made the patient feel more supported and less isolated to the cystic fibrosis hospital team, gave a sense of security in seeing their health care providers face to face, and made it convenient to discuss health issues. Compared to the control group, no differences were seen in quality of life, anxiety or depression, admission to the hospital, clinic attendance, or the use of intravenous antibiotics.17 More significantly, there was a positive correlation in the perception of body image for those in the telemedicine group compared to the control group after six months of interaction.

Pabinger et al. expanded on this ideology by evaluating if diagnosis and therapies of outpatients in general surgery can be assessed using a mobile healthcare communication app instead of personal contact. Out of 225 adult surgical outpatients, 84% of telemedical diagnosis matched the on-site diagnosis, 76% proposed the same therapy, and 94% did not receive any inferior treatment.18 In the remaining 6% of cases, the telemedical therapeutic regiment had the potential to harm, under, or over treat the patient.18 Despite a decreased waiting time and patient frequency, this fractional percentage emphasizes the potential dangers in completely dehumanizing healthcare consultations.

The pandemic stimulated the advancements of telemedicine in a healthcare system that is resistant to change. A standardized, secure, and HIPAA-compliant form of telemedicine has yet to be standardized, but even more concerning is the lack of standardized training (or lack thereof) for all physicians. Despite the widespread acceptance of, either due to fear of the pandemic or in order to opt for general convenience, the physician-patient relationship should not be taken for granted or lost in virtual technology. A number of pilot programs have opted to balance traditional and telehealth follow ups based on a case-by-case situation, however other primarily virtual programs threaten the longstanding respect and commitment individuals have for their healthcare providers. As the post-pandemic era continues to unfold, physicians and patients should work to honor and nurture that vital relationship whether it be in person or via telehealth.